On Timeouts in Distributed Systems

Here’s a brain dump of thoughts I kept in my head about timeouts in distributed systems.

Longer timeouts (for downstream dependencies) are tying request handling threads in a service for a longer time which means that request handling thread pool is going to get exhausted faster, which at point of exhaustion kicks-off a cascading failure in the upstream services until the whole system becomes unavailable.

Upstream services exhaust thread pool faster

Upstream services have a higher chance of this happening since they are, by definition, waiting longer for the response compared to downstream services (response time of a given service is proportional to the number of downstream dependencies) and thus needs to be planned accordingly in terms of thread pool capacity.

Timeouts don’t help with business availability

Also, timeouts help with system (service) availability, but not necessarily with the business availability. If we have A→B→C service chain and B times out for A, then A is going to be able to accept requests, but not to fulfill them. Technically speaking service is up, but not able to fulfill use case (business capability), which is the same as if service was down. So, timeouts don’t help us with business availability in this case, but can help us with:

- allowing downstream service to recover faster and

- being able to respond to requests that don’t go down the path of B→C in order to fulfill the given use case

Services with higher fan-in factor bring more of a system down

It also depends on the fan-in factor of a given service. Usually, the more downstream we go, the higher fan-in we have. This indicates services that we need to be more careful about, since when they become unavailable they are bringing more of a system down with them than the services that have lower fan-in factor. Meaning, the services with high fan-in factor are bottlenecks in terms of the system availability and thus should have more aggressive timeouts towards the downstream dependencies in order to release request-handling threads faster and not bring the rest of the system down with it.

Timeouts and the Theory of Constraints

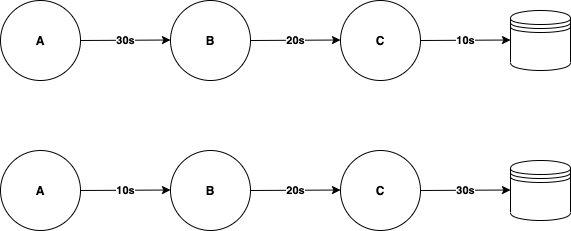

Consider two following scenarios:

Numbers on the arrows are timeouts that are specified for each downstream service. C has timeout of 10s against database, B has timeout of 20s against C and A has timeout of 30s against B. In case database hangs because certain query takes longer time to execute, C will time out after 10s and this is going to propagate upstream. Meaning, request-handling threads in B and A are going to be released back to the pool after ~10 sec.

In the second case though, C has timeout against database that is longer than timeouts in the upstream services. If C hangs for 30s, B is going to time out against it and release its thread after 20s and A is going to time out and release its thread after 10s. What usually happens is that A and B have retries in place, so will fire another downstream request towards C, so the same thing is going to happen for another thread in C. What this means is that exhaustion rate of thread pools in A, B, C is different (exhaustion rate in C is the fastest, while in A it’s the slowest) and that services are running at different speeds. These retries in the upstream service can be automatic or manual, where user sees that their request didn’t go through and then they initiate another request (refresh the page, click the button again, etc.).

The Theory of Constraints (ToC) defines the constraint as the slowest resource in the system. We identify the constraint of the system by the biggest pile of work waiting in front of it. In this particular case it’s the database since the queue of requests in front of it (requests sent from C to database) is building up the fastest in the whole call chain. When we have a constraint in the system (sometimes called the bottleneck), ToC says that in order for the system to have the highest throughput, all other parts of the system (non-constraints) have to run at the speed of the constraint. If non-constraints run faster that the constraint (called local optimizations in ToC), system as a whole is not only not going to run faster, but it’s actually going to start running slower and slower. So the system deteriorates not in spite of the upstream services trying hard to call the downstream service, but because of it!

Point I’m trying to make is that every (distributed) system has a constraint and in order for it have the highest throughput and avoid whole system outage, timeouts from the upstream services must not be shorter than the timeouts of the downstream services.

There’s also a concept of Drum-Buffer-Rope in the Theory of Constraints.

Drum is dictated by the rate of processing of the constraint (database).

Buffer is inventory in front of the constraint (number of threads in queue in front of the database).

Rope serves as a signal for the top most service to allow the next request in the call chain to pass.

So, the constraint should be the one signaling to the rest of the system when to allow the next request. Meaning, database should be the one dictating rate of requests that we allow into the system.

Circuit breakers and limiting amount of retries is actually the application of this idea, although we can even do better and not even accept requests at the entry of the system if the constraint is hammered. It allows for even quicker recovery during the problem and once starts picking up the pace again.

Timeouts and business value

Also, if there are, say, 2 downstream endpoints that a given service calls and one of those is for a use case which is, from the business value perspective, more important than the other one, then the recommended heuristic is that the timeout for the less important one should be more aggressive. That’s because duration of the timeout for the downstream dependencies is directly proportional to the rate/speed at which we’re going to eat up the request-handling thread pool in the service. We don’t want less valuable functionality to eat it (faster) and jeopardize the more important functionality (more valuable downstream endpoint) of becoming unavailable.

Having in mind previous points, you can create a map of business risk distribution across the system by weighing each service in terms of:

- its business value

- business value of its upstream services and

- fan-in factor

Business risk of a given service = (fan-in factor) x (business value of a service) x (business value of upstream services)

That can give you valuable insight into where you should put most of the focus and effort in terms of the resillience and availability.

When multiple teams are collaborating in the same service, they might not know how the downstream endpoints compare as for the business value, so it’s important to have this conversation across teams collaborating in the given codebase in order to maximize the amount of residual value available to users in case of (inevitable) problem in the system. The same conversation should also happen inside a single team if that team is the only one owning a given service which calls downstream services.

Timeouts and (suboptimal) system design

Also, a need for long timeouts (I’d say longer than a second) is probably an indication of a suboptimal system design and should be reevaluated from that perspective before proceeding.

An important thing to always keep in mind is that availability of an end user request (use case) that includes three downstream calls (activation path of 3) is:

(availability of A) x (availability of B) x (availability of C)

Having in mind that availability of each service is by definition <1, that means that with every additional downstream service dependency, availability of the use case goes down and timeouts are not going to help you out in case you’re not having this fact on top of your mind whenever you’re designing or extending a distributed system.

Also, worth pointing out is that often times it’s possible to avoid the desperate need for resiliency patterns (timeouts, bulkheads, circuit breakers, etc.) by rethinking the design of the system, e.g. pulling out the vertical slice (use case) in a single or very few services, rethinking the boundaries of the services, going from sync to async (less preferable in case you have your service boundaries wrong), etc. Meaning, a heavy need for relying on resiliency patterns is very probably an indication of a suboptimal functional decomposition of a system.